Download the presentation

In looking forwards it is important to learn the lessons of history.

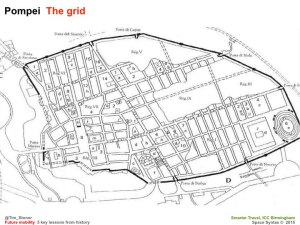

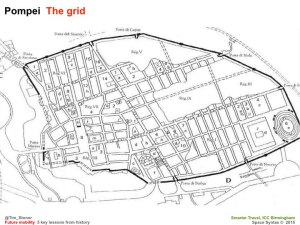

Look at Pompei. A city built for efficient mobility.

A model of the 1st century with lessons for the 21st century.

The grid – no cul de sacs. Built for mobility. Built for commerce.

More or less rectilinear – not labyrinthine. A layout that brains like. Easy to wayfind. Hard to get lost in.

A Main Street with shops – no inward-looking shopping malls. Active frontages. About as much surface for pedestrians as for vehicles – the right balance for then. Perhaps also for now?

And shopkeepers of great wealth! It was not a compromise to open onto a Main Street. It was a sound commercial investment. Who would turn their back on the flow of the street?

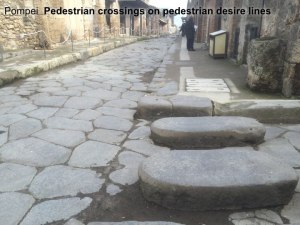

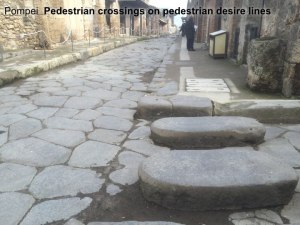

Pedestrian crossings! The deep kerbs channel water when it rains, flushing the dirt from the road and keeping it clean. Integrated infrastructure.

Pedestrian crossings that are aligned with pedestrian desire lines – not following the convenience of traffic engineers’ vehicle turning arrangements. Pedestrians first because its the pedestrians that carried the money, not the vehicles.

A small, pedestrian only zone in the very heart of the city. No bigger than it needs to be…

…unambiguously signed that this is where you have to get out of your chariot and onto your feet.

Pompei: a city of great streets – great street sense.

But in recent times we lost our street-sense.

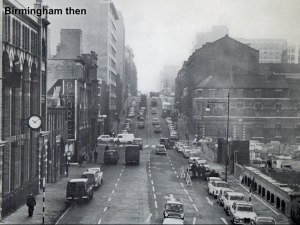

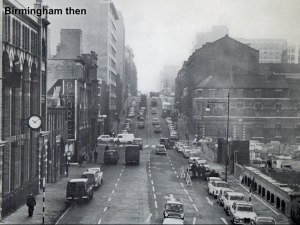

Look at Birmingham then…

And now. What happened to our street sense?

And Birmingham was not alone.

Look at US cities:

What they were…only 60 years ago – recognisably like Pompei: simple, rectilinear grids.

Then what they became…

We became entrapped by traffic models.

And a love-affair with the car.

We need to regain our street-sense.

Fortunately this is happening.

Trafalgar Square,

Nottingham.

At the Elephant & Castle, this design puts the pedestrian crossings on the pedestrian desire lines – just like those crossings in Pompei. We’ve talen pedestrians out of subways and given them their proper place at street level, next to the shopfronts. We’ve made the humble crossing an object of beauty, spending many different budgets (landscape, planting, pedestrian, cycling, highways) on one project so that each budget gets more than if it had been spent separately.

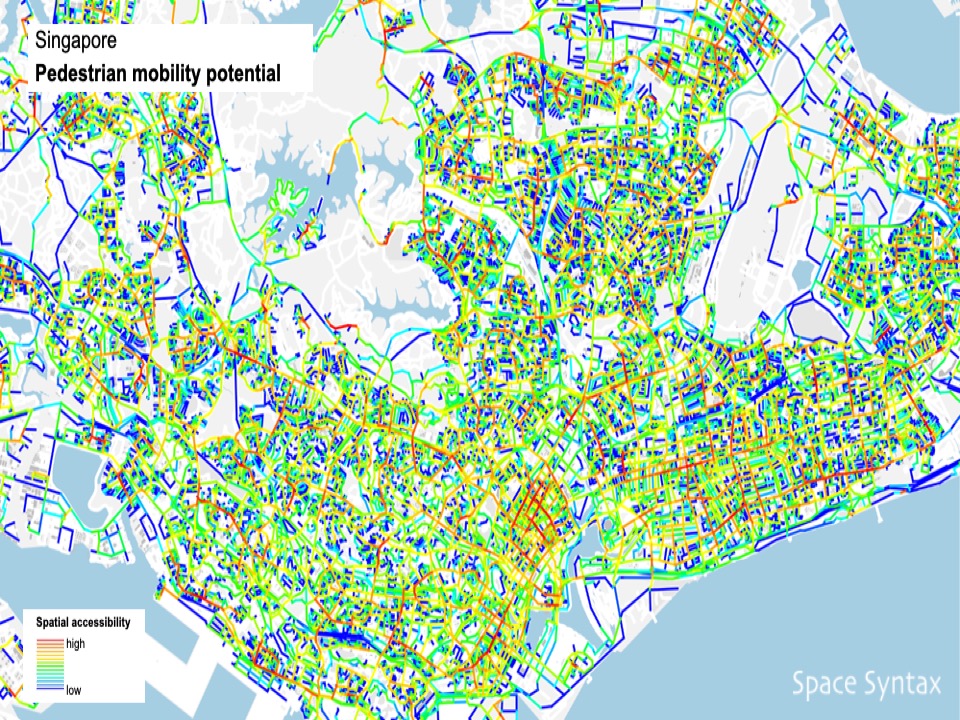

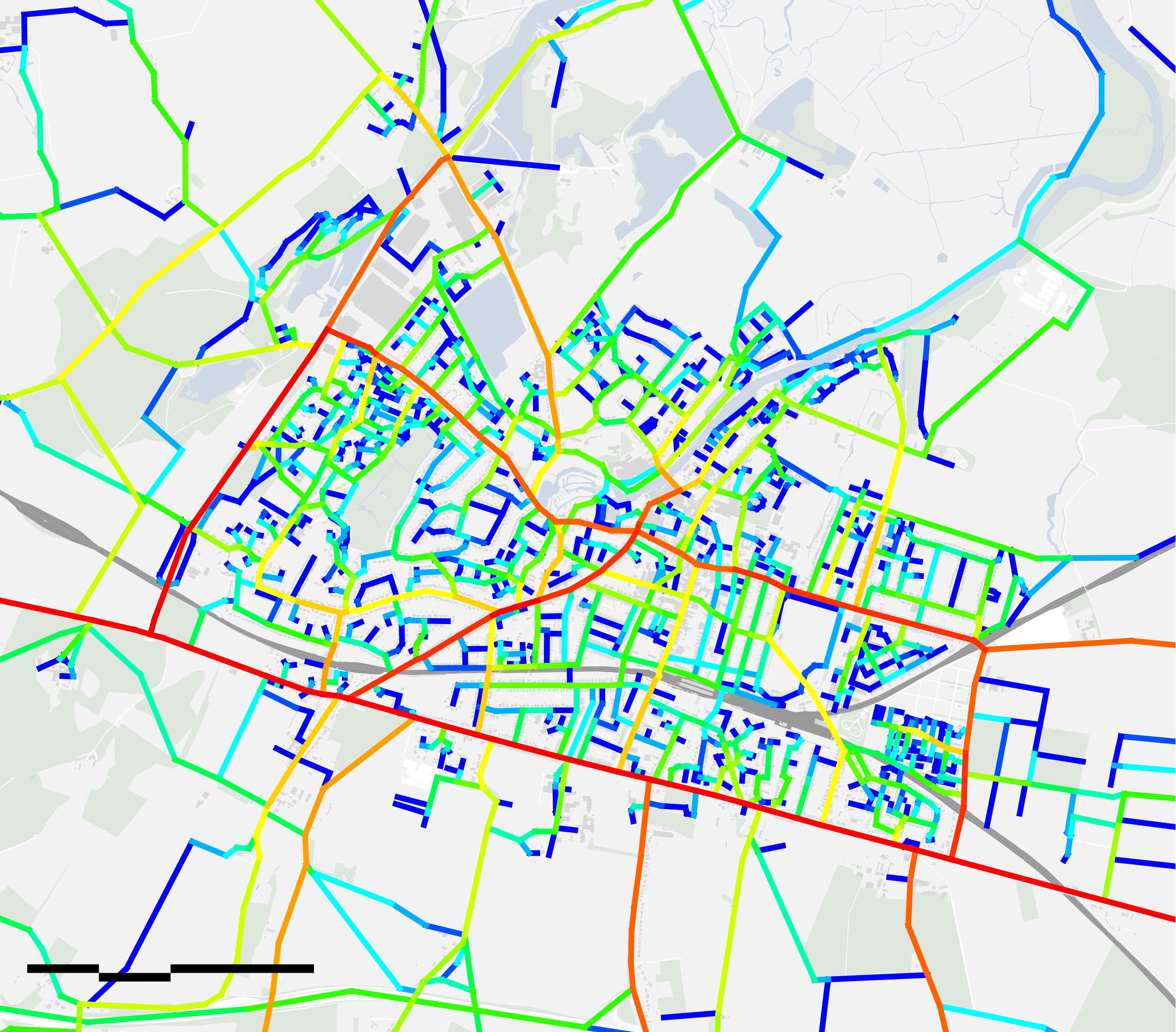

This new approach – a rediscovery of street sense – has been made possible through advances in science that have made us see the errors of previous ways.

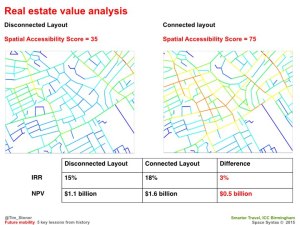

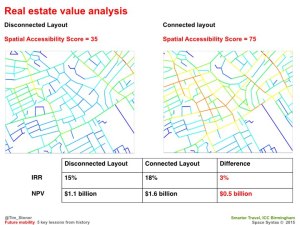

The more we look into this the more we find of value: for example, how connected street grids create higher property values in the long run.

And Birmingham has pioneered this science:

Brindley Place – the bridge on the straight east-west route – a lesson from Pompeii! It may seem obvious today – because it’s a natural solution – but it wasn’t obvious to some people at the time, who wanted the bridge to be hidden round the corner because, they said, there would be a greater sense of surprise and delight! What nonsense. We had to model the alternatives and show just how powerful the straight alignment was.

We still have to do so today. Many urban designers and transport planners have been slow on the uptake. The average pedestrian gets it immediately. What does that say for our professions?

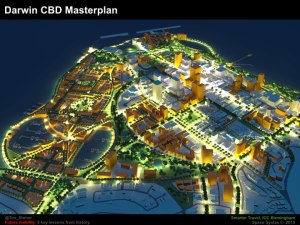

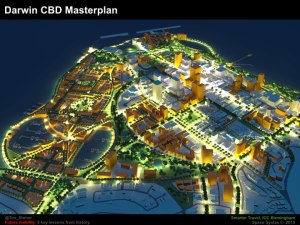

Now cities all over the world are recovering their street sense, creating plans for their expansion that are street-based, not mall-based.

In time to accommodate a new, two-wheeled chariot: the bicycle.

SkyCycle – a new approach to urban mobility. Creating space for over half a billion cycle journeys every year. Constructed above the tracks, allowing smooth, predictable, junction-free movement between edge and centre. Developed by a consortium of Exterior Architecture, Foster + Partners and Space Syntax.

Adding to cycling at street level – not taking it away.

Recently, at the Birmingham Health City workshop,a discussion about the location of healthcare facilities quickly became one focused less on hospitals and wards and more on streets and public spaces. On “free”, preventative public health rather than expensive, clinical curative care. Free in that it comes as the byproduct of good urban development.

Rob Morrison’s drawing of the Birmingham Boulevard…

…an idea to turn the Inner Ring Road into an active street.

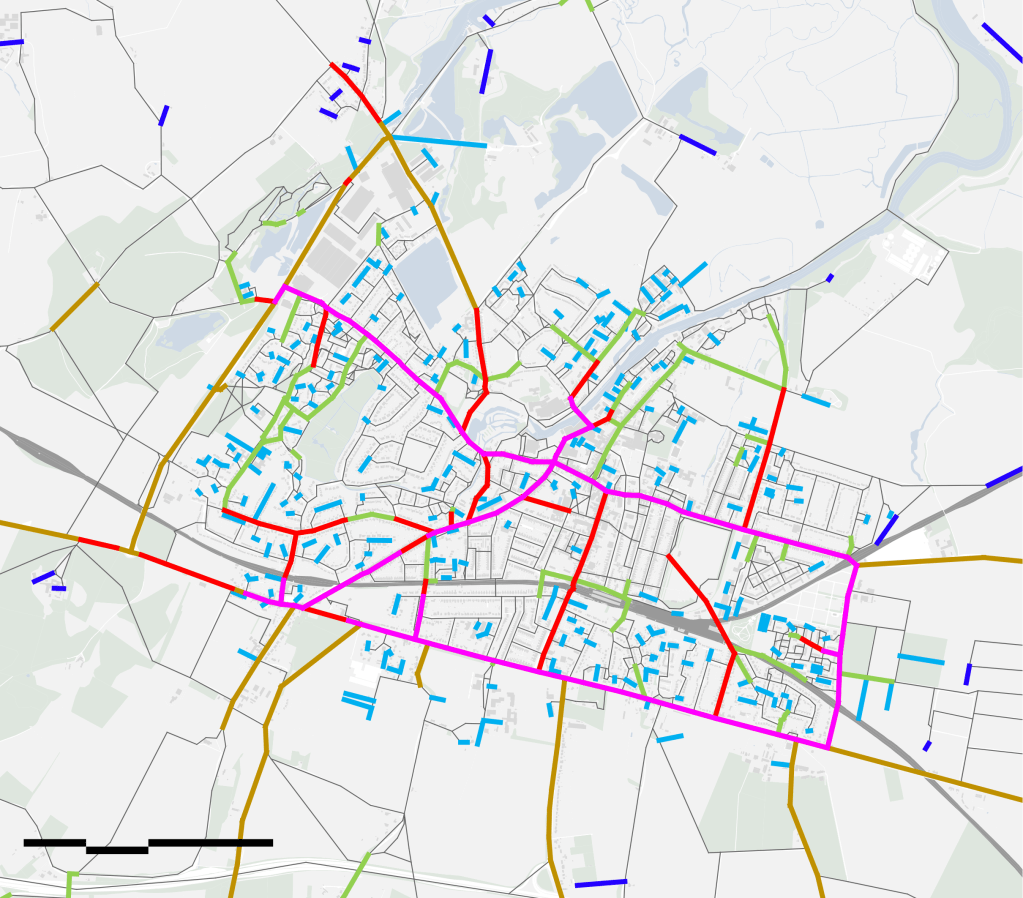

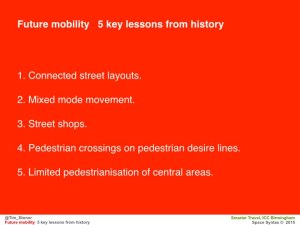

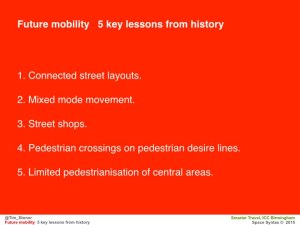

And to achieve this there are clear principles to follow:

1. Connected street layouts.

2. Mixed mode movement – not separated by tunnels and walkways.

3. Active streets ie lined with street shops not mall shops.

4. Pedestrian crossings on desire lines, not where it’s most convenient for traffic turnings.

5. Limited pedestrianisation of the most important civic areas.

A thought – yes Pompeii was a city of commerce but the houses of the city are filled with references to literature, poetry, music: the arts.

Huge cultural value.

After all, this is the important, aspirational aspect of living in cities that comes with the efficient mobility that results from pragmatic planning: the grid, mixed modes, active frontages on main streets and special, limited, high intensity, pedestrian only places.

When we get this right we have time to truly enjoy ourselves in the arts and sciences. In culture. That is truly great urbanism.

Download the presentation