Designing Resilient Cities – notes from Day 1

A note from the Vice-Mayor for Infrastructure to the Mayor

cc

Vice-Mayor for Sustainability

Vice-Mayor for Engagement

Vice-Mayor for Disruption

The Public

Avalon faces the risk of functional failure. The only way forward is to change.

Our infrastructure is inefficient. It needs to become efficient. This is not just a question of maintenance. There won’t be enough money to run the transport network, supply water, remove waste, provide broadband. Unless the city either shrinks to a size its current economic structures can afford; or grows to create a larger tax base – so long as the city can retain control over how that tax is spent.

The view of the infrastructure team is that Avalon should grow. But not off the back of its existing industries. These are running out of steam. The industrial infrastructure of the city needs to expand and to reinvigorate. Creative industries will be central to this.

A new population will come to Avalon. A younger population, joining the older, wiser and more experienced population that built the city’s wealth in the 20th century. Joining young people who, having grown up in Avalon have chosen to stay there rather than take the increasingly well-trodden path elsewhere. The city has seen too much of this. Its infrastructure of talent must be rebuilt.

And these people will need somewhere to live. Houses that are affordable. We need to build.

But this does not mean ever further sprawl into our precious countryside – which is too beautiful and too productive to become a building site. No, it means building on our existing urban footprint. We need to find space within the city, not outside. Some of our redundant industrial sites will provide excellent places for new housing: close to transport infrastructure, with excellent, ready-made supplies of water and power. We need to look hard at the vast city parks that were built many years ago and have simply not worked as they were intended – they have harboured crime rather than nurtured culture.

And culture is central to what we must do. Avalon needs to recapture the spirit in which it was first built: a pioneering spirit where anything was possible. Music, art, sculpture, performance: song and dance – we were good at it when we tried. The future memories of Avalon will be built on the strength of the cultural infrastructure that we put in place in the next few years.

And to achieve all of this we need to change the way that we make decisions in the city. No more top down dictats. We need a governance infrastructure that involves everyone: participatory planning, budgeting and decision-taking. An elected mayor for a start.

_____________

Components of infrastructure

Demographics

Life satisfaction.

Transportation

– on ground

– above ground

– below ground.

Health

Not just

– physical buildings

but also

– insurance.

Security

– police

– building protection

– wellbeing.

Equality

Utilities

– water

– gas

– waste

– digital.

Green environment

Culture

– facilities.

Place

– connections.

Diagnosis

Avalon is…

Set in its ways.

Boring.

No desire to change.

Reliant on the public sector.

Declining core industry.

Few common places.

Weak cultural identity.

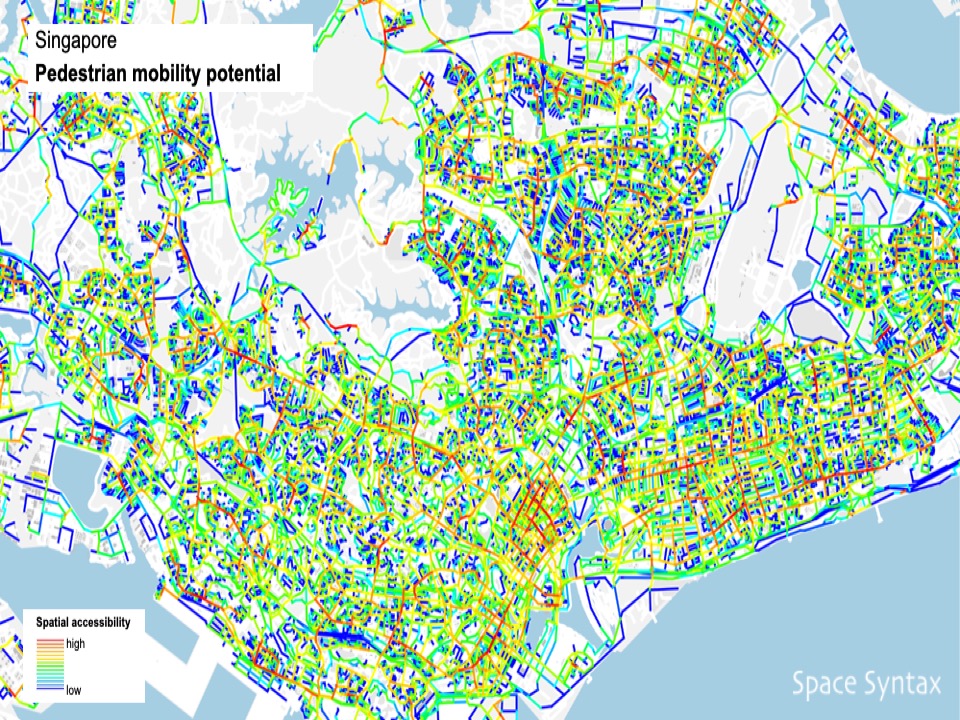

Car-reliant.

Running out of time.

Risks

Functional failure

– not enough revenue to run the city.

Fragmentation

– in governance, leading to rivalry and underperformance.

Disenchantment

– no sense of belonging.

Disconnection

– of people from planning

– reinforced by physical remoteness of outlying centres.

Civic unrest

– class distinctions, unintegrated, breeding distrust.

Poverty

– when older population retire.

Complacency

Cultural sterility

– no fun

– no stimulation

– no sense of belonging.

Industrial stagnation

– no innovation.

Objectives

Governance

– committees to reflect areas

– directly elected mayor

– participatory planning

– devolved management of infrastructure.

Identity

– common vision

– campaign

– slogan.

Industry

– built around the creative industries

– attracting people from outside, not only serving existing population

– business development area

– enhance links to surrounding agriculture.

Public realm

– enhanced

Consumption

– reduce

– reuse

– recycle

– multiple uses of each infrastructure asset e.g. reservoir is boating lake.

Housing

– more affordable.

Density

– intensify existing urban footprint rather than further sprawl.

Connectivity

– revitalise the centre.

Transport

– integrate existing modes.

_____________

Designing City Resilience is a two-day summit at the RIBA, 17-18th June 2015. Avalon is one of four imaginary cities being looked at during the event in a creative approach that breaks the mould of typical, presentation-only conference agendas. By engaging in a rapid prototyping exercise, delegates immediately test the ideas they have heard in the keynote presentations and on-stage discussions. They also bring to the event their own international experiences.

The result is a two-way, creative conversation that produces a richer outcome: a set of designs for the transformation of the physical, spatial, environmental, industrial, educational, healthcare and governmental structures of the four cities.