Notes from a response to questions from the Strelka Institute.

How would you describe the situation with the permeability and connectivity of city spaces today?

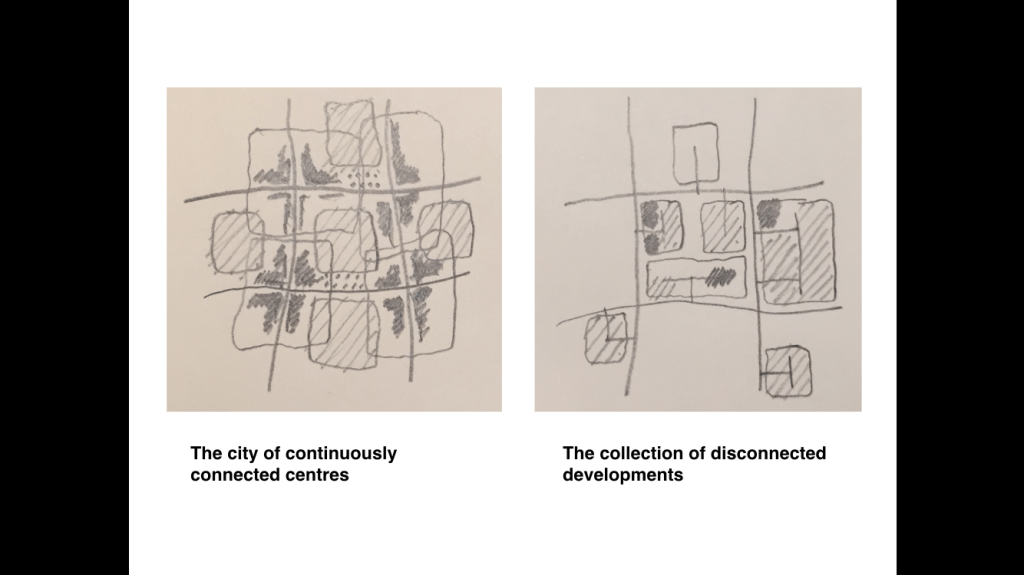

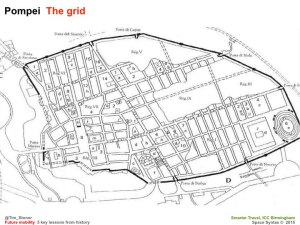

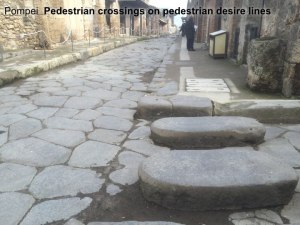

There is no single state of permeability and connectivity in the contemporary city. Instead we find two main types of urban layout: first, the finely grained, continuously connected street network in the historic city and second, the system of largely impermeable housing estates separated by fast-moving roads in the 20th century city.

In the historic city, space is well used. Most space use is movement and most movement is through movement. Movement supports commercial activities, which locate themselves on the principal streets where footfall is greatest. Movement brings people to places of opportunity – to buy, sell, exchange and interact. Effective exchange and interaction drives urban economies, social networks, cultures and innovations.

In the 20th century city, the large, impermeable blocks of the housing estates do not encourage through movement. People move around the estates rather than through them. As a result, commercial activity is undermined, with its market divided between people moving locally inside the estate and those moving globally around it. Commercial activities are more likely to fail, especially inside estates where the marketplace is too weak. Instead, shops form at the entrances to the estates and on the surrounding roads. Since these roads have often been designed to favour the car, the shops are likely to be car-based, with large parking lots that further separate local people from them.

A further, social consequence of this is that local people do not see people from outside the estate on the regular basis that people in traditional streets take for granted. The effect of this is to create social isolation and fear of strangers in estates.

The irony is that the inward-looking urban block was created purposefully to foster a stronger community spirit. Traditional streets were considered to be noisy, dirty and dangerous. 20th century town planning’s idea was that, if life could be created away from streets then people would be cleaner, happier and safer.

It is the greatest tragedy of 20th century international planning that its well-intended model of urban living has failed. Indeed it has done the opposite: creating highly negative social and economic outcomes for all people with perhaps the exception of the super rich for whom social and economic relations are formed in different spatial contexts.

Connectivity is closely connected with the structure of property ownership, how will it change in the next 5 years? Will it shift towards privatisation of public spaces? And what will be the case 20 years from now?

Undoubtedly the next decade will see more private spaces set within gated communities. Such forms of urbanism are still favoured by developers and aspirational residents for whom the idea of living in a cleaner and supposedly safer environment is expected to make them happier. The history of 20th century failure may not be considered to be relevant, perhaps because of a belief that it happened somewhere else, or in a different socio-political era, or because new digital communications technologies can effectively span the spatial divide between such places and their urban settings.

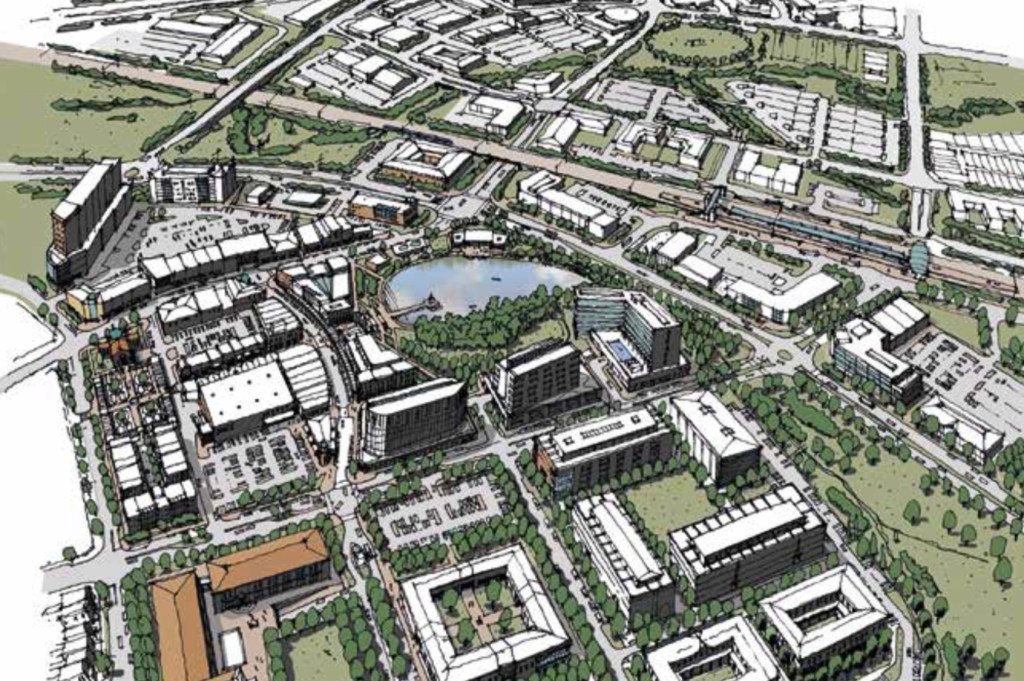

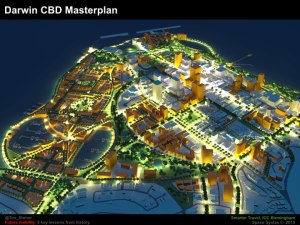

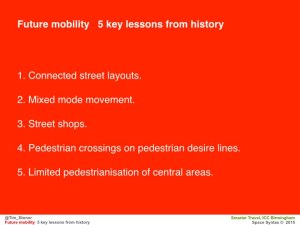

At the same time, the resurgence of traditional street design will see more places created that look more like the continuously connected form of the historic city. This trend can be seen in cities as diverse as Beijing, London and Dubai, where permeable street networks have been created by commercial property developers as well as public municipalities precisely because they are seen to deliver places that are popular with people. The social and economic benefits of a street-based approach have been witnessed with a combination of satisfaction and surprise.

Perhaps the most significant impact on the form of urbanism in the future city will come from the digital technologies that will record and analyse the outcomes of both approaches – the gated community and the open street network – and demonstrate with evidence how each performs.

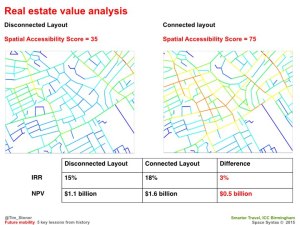

My clear view is that the continuously connected street network will outperform the gated community in terms of Urban GVA, making a greater contribution to the overall social and economic value of the city. The emerging Science of Cities, in which my company Space Syntax has been a pioneer, is one of the key areas of future urban practice that will cut through the inaccurate claims that have been made about the benefits of estates – claims that have been promoted by architects and urban planners throughout the 20th century, based on the passion of their beliefs rather than on the evidence of facts. Urban analytics will transform urban practice over the next 20 years, shaping a new, evidence-rich approach to architecture and town planning and, crucially, returning a highly effective, street-based form of urbanism to the position it had held for centuries before professionalised town planning imagined it could do better.

During our work for the classification of Moscow streets we highlighted three different zones of the city: centre (inside the Garden Ring), middle zone (between the Garden and the Third Transport Rings), and periphery (outside the Third Ring). The pattern is completely different in these zones. Could you comment on the implication of global trends of connectivity in the city on different zones in Moscow?

No city is the same from its centre to its edge. Or, more precisely, from its centres to the edges of those centres because cities are formed of multiple centres that create a system of connected urban quarters. The quality of the connections between centres is a fundamental determinant of overall urban performance, having a strong bearing on whether people are more likely to walk and cycle between neighbourhoods and whether those links will be effective places for social and economic activity. When centres are continuously connected to each other through a set of connections with a regular grain then it is likely that many, if not all of these will be suitable for walking and cycling as well as driving along.

Cities like London and Paris are composed of multiple centres that have distinct centres of differing characters yet are continuously connected to each other. Indeed it is the magic of such cities that it is possible to move from one centre to the other in such a subtle way that you are uncertain exactly when you have left one centre and entered another. The connective “tissue” between centres is typically comprised of residential streets, which therefore link to – and carry movement belonging to – multiple centres. People may identify more with one centre than others but they are provided with a choice of more than one. And,min doing so, they interface with people from more than one centre. The benefits of this arrangement are simultaneously social and economic.

Such choice is denied by the 20th century city of separated estates. People living in one estate have limited, if any direct access to the centres of other estates. Increasingly, the roads that connect between estates are hostile to pedestrians and cyclists. Social and economic life is suppressed.

All cities are systems of linked centres that each work in individualistic, local ways but that also form an overall city system. Within this city system, the centres have a hierarchy with more central centres typically supporting greater economic activity than centres at the edge. This is not only because more central centres are larger but also because these centres are surrounded by a larger number of other centres than are peripheral centres.

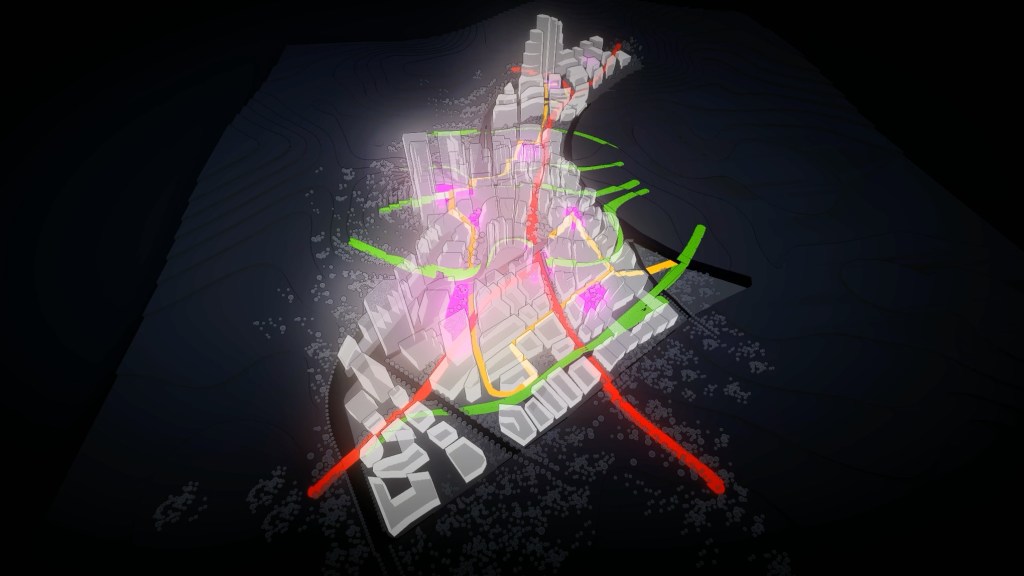

In the case of Moscow, Space Syntax analysis would be used to examine the hierarchy of centres, the quality of the connections between them and the degree to which spatial connectivity is directly related to social and economic performance. Data on economic performance – such as land value, property transactions, commercial performance, retail sales – would be correlated with measures of spatial connectivity – such as spatial centrality (choice) and betweenness (integration) at a range of spatial scales. These Big Data sets would be interrogated in order to form a diagnosis of the current spatial conditions. On the basis of this diagnosis, a set of spatial planning principles would be created that would lead to the production of a spatial vision for the city. We anticipate that this form of data-rich, evidence-informed planning will become normal in the next 20 years.

While improving and redeveloping city streetscape how should trends in the connectivity and permeability of city space be taken into account?

Space Syntax analysis shows how patterns of spatial connectivity have profound influences on the social and economic performance of all cities. The hierarchy of spatial connections influences:

movement patterns of cars, cycles and pedestrians

– public transit demand

– land use performance

– land value

– transport emissions.

Future urban plans should therefore be created with a special emphasis on the design of the spatial layout of the city. Opportunities should be identified to strengthen the network of streets and open spaces, pursuing an overall objective to create a city of continuously connected centres. Constraints should equally be identified so that reasonable plans can be made.

“Spatial geometry” standards should be set for the number and frequency of connections as well as for the geometrical means by which centres can be most effectively connected ie first, a small set of longer, more direct connections (the “foreground grid” of boulevards and high streets) that will carry larger volumes of people and therefore be suitable for commercial uses and second, a large set of smaller, less direct connections (the “background grid” of local streets) that will carry smaller volumes of principally residential movement.

Once these spatial geometry standards have been established then further standards of urban design quality should be set – but not before. High quality urban design in the form of green landscape, seating, signage me surface treatment will not create high quality urban performance if the spatial layout geometry is weak.

The living city is built on human interaction. Without this, the city is dead. Human interaction relies on effective movement corridors and effective places of human transaction. Effective street connectivity is a critical determinant of the living city.